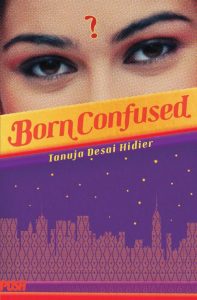

As an author, I am always on the lookout for books that inspire me creatively and touch me personally. I hit the literary jackpot when I discovered the much praised novel, Born Confused. It is a provocative coming-of-age story about transcending cultural boundaries, penned by Indian-American author and music artist Tanuja Desai Hidier.

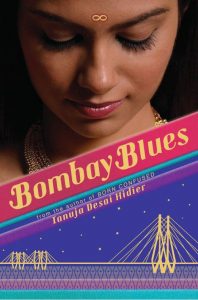

Tanuja Desai Hidier is an award-winning author/singer-songwriter now based in London. She is the recipient of the 2015 South Asia Book Award (for Bombay Blues) and the James Jones First Novel Fellowship and her short stories have been included in numerous anthologies. Her pioneering 2002 first novel, Born Confused, was named an American Library Association Best Book for Young Adults and became a landmark work, recently hailed by both Rolling Stone Magazine and Entertainment Weekly as one of the greatest YA novels of all time. Tanuja is also the innovator of the ‘booktrack’; the music video for her album Bombay Spleen (songs based on Bombay Blues) track “Heptanesia” is currently airing on MTV Indies.

Thanks to the wonderful world of social media, I discovered that she is a friend of my husband’s cousin, and was able to connect with Ms. Desai-Hidier for an interview. In this two-part interview, she shares the secrets behind her success as an author and musician.

What is your cultural background and where did you grow up?

I don’t know that I’m done growing up! (Though, vertically speaking, this may be the case.) My mother is Bombay born and raised; my father, from Gujarat, though born in South Africa, where he lived a few years as a child. I was born in Boston, lived in Bombay a couple of years as a baby, then grew up in the USA, in a small town in Western Massachusetts (home of Friendly’s ice cream!).

Later, I went to University in Providence, Rhode Island, then lived in NYC for many years, with the exception of one spent in Paris—where I was neighbors with the man who would become my husband and jeevansaathi (even frequenting the same boulangerie and Laundromat, and friends with the owners of the same fondue restaurant!)…seven years before we met at a party in NYC!

We’ve now lived in London since just after our wedding in 2000, and are parents to two London-born Indo-Franco-Belgo-Americano daughters (sounds like a next-generation Starbucks extravaganza!).

Your first novel, Born Confused, was published in 2002. What was your inspiration for writing the book?

With Born Confused I wanted to fill a hole that had been on my childhood bookshelf, with a South Asian-American coming-of-age story. An exploration of ‘brown’. (And, many years after that, one of the reasons I wrote Bombay Blues—an exploration of ‘blue’—was to move beyond the skin.)

I grew up in a small, predominantly white town in Western Massachusetts. We were the first ‘brown’ people—South Asians—there, though there were a couple of African-American families. At that time there were no people of our particular color anywhere: on bookshelves, in magazines, in bands, on T.V., even forecasting the weather. (Add to that the fact my parents were the first from both sides of the family to immigrate to the USA.)

When I was a child, on the US Census there was no South Asian American category. I was always confused when I’d have to fill out forms like this: about race. Was I Asian/Pacific Islander? More often than not I’d tick off ‘Other’. I wasn’t really tortured by these thoughts; had a daydreaming childhood in a loving family with a good set of friends. In fact, this daydreaming was perhaps why I felt ‘different’ if at all—this tendency to get lost in books and stories and my own imagination.

Though I was one of only a handful of children of ‘color’ at my school (that term didn’t exist then: we were two black kids and two brown), I don’t really remember being that aware of being so, at least from a racial and cultural point of view. But in retrospect this otherness—an otherness to myself, possibly, even more than vis a vis other kids—had manifest itself. For example, a couple childhood Halloweens I dressed up…as an Indian girl. Or at least what I assumed an Indian girl dressed up like, from the little saris and bangles my relatives in India sent back to me for Diwali…which we didn’t celebrate (Halloween yes)!

Looking back on this fact now, many years later, I see that in a way it summarizes the feeling of Dimple Lala: This not quite fully feeling Indian…nor American. Like Dimple, when I felt ‘different’ in India, I assumed it was because I was too American. And when I felt different in America, surely it was because I was too Indian.

Or, conversely, neither American nor Indian enough.

Really, this later was my main struggle as a writer: Doubting whether I had what it took to write a novel. Utter confusion about what to write, how to express my cultures. In short: Not recognizing the value of my own story. I’d realized at some point in NYC that I wanted to write an Indian-American story—but felt I wasn’t Indian enough nor American enough to do so. One heart-pouring night in the East Village out with a friend I was lamenting this fact to her when she turned to look me straight in the eye and said, “That’s your story.” It was a pure lightbulb moment:

Something clicked that night,…though it took me years to figure out what to do about it. This idea that, though I’d never fully felt a part of either side of my hyphen—Indian-American—that was a part of being part of it.

That what I’d seen as a lack of a story was a true tale to be told itself.

Can you explain what an ABCD is?

Yes! Born Confused is a South Asian American coming of age story that follows aspiring photographer Dimple Lala through a New York-New Jersey summer that turns her world on its head, as she tries to figure out how to bring her two cultures together without falling apart in the process. The title comes from ABCD, or American Born Confused Desi (person of South Asian origin), a term South Asians from South Asia have to describe these second and third generation kids (well, adults, many of them now) who are supposedly confused about where they come from. (The alphabet goes all the way to Z, and there are two versions of it! You can hear it in full here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ei0tyw7u09M )

When I first heard the term ABCD, and directed at me, however affectionately, by university friends from Pakistan and India—my first experience of ever having desi friends– my reaction was mixed: a sense of excitement that there was a term for ‘us’, we South Asian Americans who till that point had seemed to inhabit a neither-here-nor-there-space. And as well, a sense of indignation: at being named (and in a somewhat derogatory manner) by people who were not in fact part of this ‘other’ space.

In the late 90s, I discovered the first generation-American South Asian arts scene in NYC (that’s also when it came into being) almost overnight, when a short film I’d made with a South Asian protagonist began to play the festival circuit. And almost overnight I met more South Asians than I’d ever known in my life, up to all kinds of creative mischief. And things began to click.

The late 90s was an incredible moment in terms of the subculture’s gaining of critical mass and momentum: We witnessed the flourishing of South Asian Studies departments, the birth of the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective, South Asian Student, Journalist, Lesbian & Gay associations, South Asian film festivals. And, crucially, a South Asian club scene. Parties like DJ Rekha’s Basement Bhangra and Mutiny created spaces where the twain could meet: Missy Elliott and Malkit Singh, Talvin Singh and Lauryn Hill together as if they’d never been apart.

Remix. We mix.

It was an eye-and-ear-opening experiencing living this moment.

One aspect I loved about this particular breed of partying was how the politics of these people—of us! finally an us!—was very much intertwined with the music, the parties. The same folk who would be at an NYU debate arguing with passionate conviction about appropriation by day (see: Gwen Stefani. Bindi) would a few hours later all be throwing it down at SOBs for Basement.

And they sure as frock didn’t seem that “Confused” to me!

Later, part of what I wanted to do in Born Confused is turn the ‘C’ for Confused in the term ABCD into one for Creative—as this felt to me to more accurately reflect the dynamic desis who peopled the world I’d known at home, and later in NYC. People who were in fact shaping and creating the culture as they went along. As we went along.

And as humans we all do this, no matter what our background.

For we are All Born Creative Dreamers—scripting our own stories to realize our own dreams, expand and define our own space. We are all on this journey together.

Your newest book, Bombay Blues, is the next step in Dimple Lala’s journey of self-discovery. Can you talk about the book and how your own journey influenced the writing of it?

During the decade between novels—during which time I also became a mother to two daughters–I explored a few other book ideas. But in the end, I suppose I missed Dimple too much. I was wondering how where she was, what she was up to … and knew the only answer to that question would be to write it.

And Bombay, it became compellingly clear, was where I could find her.

Becoming a parent myself certainly crystallized my desire to learn this part of my own parents’ history better: the city of their courtship, of my mother’s and brother’s birth…yet a place American-born me barely knew. I longed to write my way towards this metropolis of myth and memory — and, hopefully, into it.

Though of course I wanted to explore culture — the idea of being brown among the brown — as well as place, and the cultural shifts happening within a globalized Bombay (the dynamic between the reverse diaspora and its many coexisting ancient aspects)…even more that that, with Bombay Blues, I wanted to move beyond questions of culture, or at least that kind of framework. To step out of frame: enter a more ambiguous space, in part through Dimple’s trajectory as an artist — and that of her heart.

Photographer Dimple travels to Bombay to shoot the browns — or so I thought. As I spent more time there, though, to my surprise and delight, blue began to overwhelm: initially in terms of actual sightings of that hue in Bombay. And that hue became the clue, led me to the idea of exploring the ‘bigger’ blue: music, mood. The wild blue yonder. It was a liberating and dizzying approach, exploring this city with a theoretical map that simply had a splash of color on it. It required a kind of act of faith.

So, like Dimple with her photography, my modus operandi — my unmapping map, if you will — while writing this book became this: To follow a color. All the way through. And just see what it would lead to. In loosening the coordinates in this way, I also fell upon what became one of the main themes of the book: the idea that there is no place like home…because home is not a place. It’s a sense of sanctuary; you may find it in a person, a place, a moment, a memory. We, as humans, are swimming cities; home is a direction.

How was the writing of this book different than the first?

With Born Confused I drew from the decade I’d lived in NYC—looking back in many ways on a known, however fictionalized, experience (the final book was fairly close to my original outline/plans for it). Bombay Blues was an utterly different experience: I went to Bombay in search of my story–spending several weeks there over the course of a year, and then three more years living it on the page–which was a constantly shifting, evolving creature (on day two of research trip one, my outline flew out the window!).

Which ended up being what the book is in large part about: the unplanned, the unanticipated, the unmapped. I had to drop my own map for this experience. Which –literally and metaphorically—heroine Dimple does too.

And which motherhood makes you do too! An enormous difference between the processes for both books is that I was not yet a mother when I wrote Born Confused (which took, funnily enough, a gestational nine months to write and revise). And I was the mother of two little girls for Bombay Blues (and this time, it took more than three years to write both the novel and my accompanying ‘booktrack’ album, Bombay Spleen).

But then, it wouldn’t have been this book, this story, without them.

It’s been an interesting process for me, growing older with the same character: Though two and a half years pass in Dimple’s life between Born Confused and Bombay Blues, and a decade passed in mine… funnily enough, the exhilarating and exhausting and mind-bending experience of parenthood also returned me in many ways back to zero in the identity quest, as I tried to bring together the life I’d been leading with the infinitely richer and more challenging role I was in now.

This certainly helped me return fully into outsider and constantly questioning shoes for Bombay Blues. In Bombay, Dimple is exploring the physical terrain on multiple levels: that of the landscape she’s in, but as well, that of her sexuality and physical being…both, in some ways, foreign ground.

Dimple plunges into this new old world with her camera. A question at the story’s core is how to follow your heart and your art…and what happens if experiences you begin to allow in and inhabit take you away from some of the things, people, places you love most. If your very world rubs up against your very world and creates friction—but also a spark.

Similarly, during the writing of it, more than trying to reconcile any physical places or cultural spaces, I was trying to reconcile motherhood with writerhood; freedom with (often necessary) constraints.

I needed to become a mother to return to zero, to come of age again, to learn surrender and another level of love—as nineteen-year-old Dimple (though not yet a mother herself) does.

Stay tuned for Part two of My conversation with Tanuja, coming soon…